Military Installation Names. What they were, and are, and how they got there. Part 2. Posts in Wyoming

Part 1 of this post was originally just a few introductory paragraphs before what was intended to be a discussion on Wyoming's posts, but it grew so large, we made it a separate entry. Here we go on to the second part of the discussion, which was supposed to be the main point of the discussion.

The Wyoming Posts

The Wyoming Posts

Wyoming has had a large number of military installations over the years, but most of the posts that have existed within it are long closed, with some of them closed installations for over a century. Today, there are only three really substantial full time military posts in Wyoming, with two of those being National Guard facilities. We'll take a look at those posts first.

Current Posts

Current Posts

Warren is named after Francis E. Warren, former Wyoming Senator and Governor and father in law to Gen. John Pershing. He was also a Civil War Medal of Honor recipient, an award conferred on him post war. Warren was a major Wyoming political figure during his lifetime. The post wasn't named for him at first, however. It was named for David A. Russell.

David A. Russell.

David A. Russell was a career officer and West Point graduate who was a casualty of the Civil War. Russell had fought in the Mexican War and in the West at the Rogue River War, but had no direct connection with Wyoming of which I'm aware. Russell was killed by shrapnel in September 1864 at Winchester, Virginia.

Ft. D. A. Russell was established in 1867, the same year that Russell was posthumously brevetted to Major General, and therefore just a few years after Russell's death. It retained that name up until 1930, when President Hoover had the base renamed for the recently departed Francis E. Warren.

Warren was a legendary Wyoming political figure of the late 19th and early 20th Century. He was the state's last Territorial Governor and it first State Governor. He served in the Senate for a long time, dying in office in 1929. He was also the recipient of the Medal of Honor for valor in action at age 19 when he was an infantryman of the 49th Massachusetts during the Civil War. He was John J. Pershing's father in law. The changing of the name of the post no doubt had as much to do with his long service as a politician as his military service.

The post became an Air Force Base in 1947. It is perhaps somewhat unique for an Air Force Base as it doesn’t contain a runway. It’s a strategic missile post.

This post, in the context of the times, provides an interesting example of a post being renamed. For the first sixty-three years of its existence it bore the name of the unfortunate D. A. Russell, and for the next ninety it has borne the name of Francis E. Warren. It's also interesting in that it provides an example of a post being renamed for a state political figure between World War One and World War Two.

Ft. D. A. Russell was established in 1867, the same year that Russell was posthumously brevetted to Major General, and therefore just a few years after Russell's death. It retained that name up until 1930, when President Hoover had the base renamed for the recently departed Francis E. Warren.

Francis E. Warren.

Warren was a legendary Wyoming political figure of the late 19th and early 20th Century. He was the state's last Territorial Governor and it first State Governor. He served in the Senate for a long time, dying in office in 1929. He was also the recipient of the Medal of Honor for valor in action at age 19 when he was an infantryman of the 49th Massachusetts during the Civil War. He was John J. Pershing's father in law. The changing of the name of the post no doubt had as much to do with his long service as a politician as his military service.

The post became an Air Force Base in 1947. It is perhaps somewhat unique for an Air Force Base as it doesn’t contain a runway. It’s a strategic missile post.

This post, in the context of the times, provides an interesting example of a post being renamed. For the first sixty-three years of its existence it bore the name of the unfortunate D. A. Russell, and for the next ninety it has borne the name of Francis E. Warren. It's also interesting in that it provides an example of a post being renamed for a state political figure between World War One and World War Two.

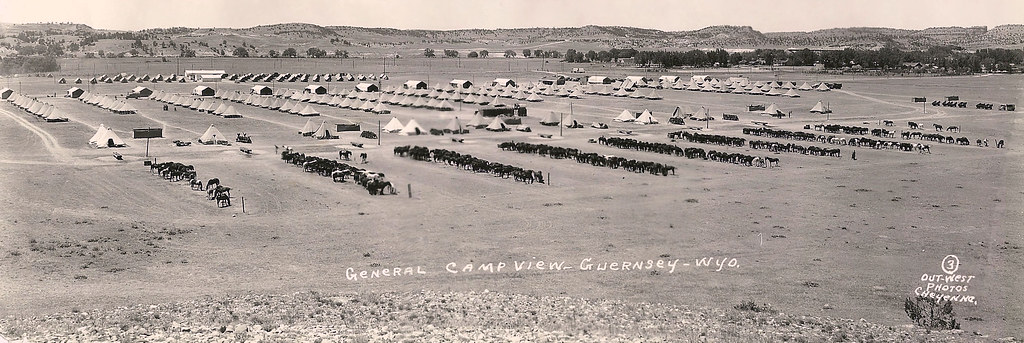

2. Camp Guernsey.

The heavily used National Guard training range is named after the town of Guernsey, Wyoming. This post receives so much use that it is, for all practical purposes, a ground combat training range in constant use by the Army and the Marine Corps, as well as the National Guard.

This National Guard post went into operation in the summer of 1938 when it replaced the Pole Mountain Training Range. The 115th Cavalry trained there in 38 and 29, and then was called into active duty in 1940. Training resumed there after the Guard was deactivated in 1945 and has continued on every since.

Guernsey itself was named for C. A. Guernsey who was a local cattle rancher and author. If viewed in the fashion of Ft. Laramie, therefore, Camp Guernsey was vicariously named for him. It's interesting that unlike the numerous camps and forts established during World War One and World War Two all around the country, no effort was seemingly made to name it after a military figure, even though numerous Indian Wars battles had been fought in the state and the state had contributed men to the Spanish American War, Philippine Insurrection and World War One by that time.

Indeed, in that context, its surprising that's never been done, even though the Wyoming National Guard has now participated, in some fashion, in every war fought since statehood.

This National Guard post went into operation in the summer of 1938 when it replaced the Pole Mountain Training Range. The 115th Cavalry trained there in 38 and 29, and then was called into active duty in 1940. Training resumed there after the Guard was deactivated in 1945 and has continued on every since.

Guernsey itself was named for C. A. Guernsey who was a local cattle rancher and author. If viewed in the fashion of Ft. Laramie, therefore, Camp Guernsey was vicariously named for him. It's interesting that unlike the numerous camps and forts established during World War One and World War Two all around the country, no effort was seemingly made to name it after a military figure, even though numerous Indian Wars battles had been fought in the state and the state had contributed men to the Spanish American War, Philippine Insurrection and World War One by that time.

Indeed, in that context, its surprising that's never been done, even though the Wyoming National Guard has now participated, in some fashion, in every war fought since statehood.

3. Wyoming Air National Guard Base.

The unimaginatively named Air Guard base in Cheyenne is also heavily used and is called simply that. It’s odd to think that this Air Guard base, which is extremely active, basically overflies Warren AFB, which as noted lacks a runway.

4. Army National Guard Armories

At least one current National Guard Armory, the one in Douglas, was named after a long time serving National Guardsman. Unfortunately, I've been remiss in recording his name and I wasn't able to find it when putting up this post. I know that he'd served for a long time before World War One, served in the war, and then after the war, as the units full time enlisted man. He was likely the only full time soldier at that post for much of that time.

The Armory in Rawlins, when it had one, was similarly named after a very long serving Guardsman, Darryl F. Acton. Acton had been the full time enlisted man and the First Sergeant of the unit for a very long time and after his retirement it was named for him. He outlived that designation, and therefore this entry more properly belongs below, as the Rawlins Armory was closed post Cold War when the National Guard was reduced in size. Today the Wyoming Department of Transportation occupied the building and the name no longer remains. 1st Sgt Action died in 2019. His military service dated back to the Korean War.

4. Army National Guard Armories

At least one current National Guard Armory, the one in Douglas, was named after a long time serving National Guardsman. Unfortunately, I've been remiss in recording his name and I wasn't able to find it when putting up this post. I know that he'd served for a long time before World War One, served in the war, and then after the war, as the units full time enlisted man. He was likely the only full time soldier at that post for much of that time.

The Armory in Rawlins, when it had one, was similarly named after a very long serving Guardsman, Darryl F. Acton. Acton had been the full time enlisted man and the First Sergeant of the unit for a very long time and after his retirement it was named for him. He outlived that designation, and therefore this entry more properly belongs below, as the Rawlins Armory was closed post Cold War when the National Guard was reduced in size. Today the Wyoming Department of Transportation occupied the building and the name no longer remains. 1st Sgt Action died in 2019. His military service dated back to the Korean War.

Former and Closed in the 20th Century.

Not counting all of the National Guard Armories in the state, of which there a large number, including many which have been replaced or simply closed over the years, Wyoming still has a surprising number of 20th Century military post that were occupied at one time. Many of these fit into the Frontier period with their establishment trailing on into the 20th Century, but a couple of them were World War Two installations. We deal with them below.

1. Casper Army Air Base.

Flag pole base of parade ground.

This enormous airfield was built during World War Two as a bomber training facility, opening in September, 1942. It was transferred to the county following World War Two in 1949 and is now the Natrona County International Airport. It continues to get a lot of military traffic including so much Royal Canadian Air Force traffic that I jokingly refer to it as the southernmost Canadian air force base.

A lot of the World War Two era buildings remain at this location, but almost all of them have been altered. A museum constructed in recent years, however, contains original World War Two era murals within it.

2. Douglas Prisoner of War Camp.

This World War Two POW camp held Italian and German POWs. Only one building remains, which contains murals painted by Italian prisoners.

This World War Two POW camp held Italian and German POWs. Only one building remains, which contains murals painted by Italian prisoners.

3. Heart Mountain Relocation Camp.

I'm not quite certain if I should regard this as a military installation or not, but given as there were troops there, I'll count it.

Heart Mountain came about when the Federal Government acted to move Japanese and Japanese American residents from the West Coast to the interior and keep them in camps. The act was illegal, but it was done, resulting in one of the more shameful episodes in American 20th Century history. One of the camps was Heart Mountain, which was opened in 1942 and remained open throughout the war, although Administration policies put in place in 1944 that started to allow for the return of the residents meant that by June 1945, prior to the end of the war, the population had been reduced by around 2,000 residents. Given that over 10,000 people were interred there during the war, that meant that few had left by the war's end and in fact the last internees left the camp in November, 1945. Given everything that occurred during the war return to their homes proved extremely difficult in many instances.

The state's reputation has been given a black mark by the existence of the camp even though the state didn't cause it to come into existence. The state did enact discriminatory laws, however, during the war aimed at it residents, who were legal residents of the US or US citizens, so the state doesn't deserve a pass on it either. The state definitely wanted the internees to leave once they could.

The land for the camp belonged to the Bureau of Reclamation prior to the war and when the camp closed it reverted to that ownership. In the 1990s efforts were made to preserve what little remained of it and a state interpretive center was opened in 2011.

It's interesting to note that in recollections by the internees Heart Mountain is fairly uniformly regarded as a horrible place, whereas generally the entire Park County region it is in is regarded as one of the nicest places in the state. This demonstrates how conditions define views. The structures at the camp were regarded as temporary and were basically tar paper shacks, something that would be difficult to live in a Park County winter even if a person wasn't a prisoner.

4. Ft. Mackenzie.

Established in 1899, this post was named for Indian War commander Ranald S. Mackenzie who is famous for the Dull Knife battle as well as his campaigns in the Southwest. This post was disestablished in 1918, with the grounds transferred to the U.S. Public Health Service in 1921, but an ongoing military presence continued on until after World War Two in the form of a Remount station. So it didn’t really completely end as a post but simply converted to an auxiliary of Ft. Robinson, Nebraska.

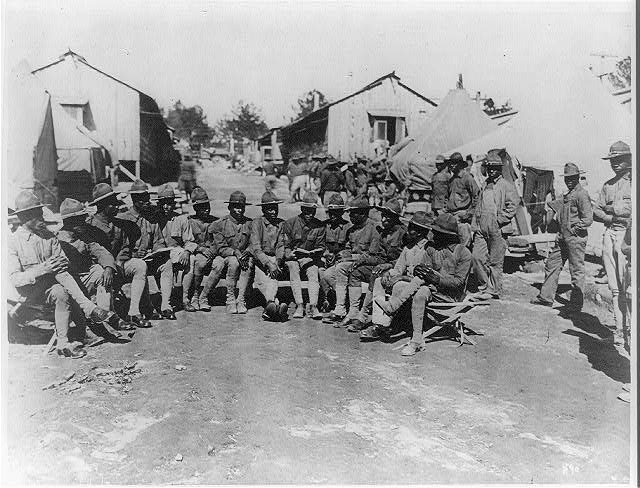

Infantry at Ft. Mackenzie, August 14, 1909.

Established in 1899, this post was named for Indian War commander Ranald S. Mackenzie who is famous for the Dull Knife battle as well as his campaigns in the Southwest. This post was disestablished in 1918, with the grounds transferred to the U.S. Public Health Service in 1921, but an ongoing military presence continued on until after World War Two in the form of a Remount station. So it didn’t really completely end as a post but simply converted to an auxiliary of Ft. Robinson, Nebraska.

This post, considered a pork barrel project at the time it was established, is one that had a long association with the military horse in that the remount aspects of this post were a major give and take for the town. The area where the post was located, Sheridan, had a substantial English ranching connection and a lot of high quality horse breeding occurred there. Polo was introduced there and it remains in the form of the Big Horn Polo Club. As noted, even after the post closed the Army remained in the form of an ongoing Remount program for years, even though the troops associated with it were technically serving on a distant assignment from Ft. Robinson. Given this, the lack of importance the fort is generally viewed with really is not fair.

Ranald Mackenzie was a famous and tragic U.S. Army commander. An 1862 graduate of West Point, he was a brilliant commander and was breveted to general in 1866. Following the Civil War he distinguished himself in the post Civil War Indian Wars. Even by the 1870s, however, he was showing signs of mental instability and was discharged from the service in 1884. While his decline was commonly attributed to falling from a Wagon while stationed at Ft. Sill, Oklahoma, there's fairly good reason to believe that it was due to the progress of syphilis. The decline of his fame was such that his death was little noted in the press, even though he'd been a very well known and followed commander only a decade before, but he was sufficiently well remembered to be honored in the form of the name of this post.

Some years ago I posted photos of Ft. Mackenzie on another site, where they'd be of interest. I just recently moved those over to one of our companion blogs, and therefore, while it may burden this thread a bit, I'm reposting them here as well:

5. Pole Mountain.

Pole Mountain was an Army and a National Guard training range located at Pole Mountain, Albany County. The range was used by both the Army and the Wyoming National Guard in the 20s and the 30s until Camp Guernsey was opened just prior to World War Two. It’s National Forest today.

It was a cavalry training range during its existence, due to the presence of cavalry at Ft. Warren and in the Wyoming National Guard during that period. The nearby presence of the Union Pacific Railroad allowed troops to be deposited at the area by train or to ride there from Ft. Warren.

Ranald S. "Bad Hand" Mackenzie. Mackenzie lost two fingers during the Civil War which is the probable reason for his nickname.

Ranald Mackenzie was a famous and tragic U.S. Army commander. An 1862 graduate of West Point, he was a brilliant commander and was breveted to general in 1866. Following the Civil War he distinguished himself in the post Civil War Indian Wars. Even by the 1870s, however, he was showing signs of mental instability and was discharged from the service in 1884. While his decline was commonly attributed to falling from a Wagon while stationed at Ft. Sill, Oklahoma, there's fairly good reason to believe that it was due to the progress of syphilis. The decline of his fame was such that his death was little noted in the press, even though he'd been a very well known and followed commander only a decade before, but he was sufficiently well remembered to be honored in the form of the name of this post.

Some years ago I posted photos of Ft. Mackenzie on another site, where they'd be of interest. I just recently moved those over to one of our companion blogs, and therefore, while it may burden this thread a bit, I'm reposting them here as well:

Ft. Ranald Mackenzie (Sheridan Wyoming Veterans Hospital)

5. Pole Mountain.

Pole Mountain was an Army and a National Guard training range located at Pole Mountain, Albany County. The range was used by both the Army and the Wyoming National Guard in the 20s and the 30s until Camp Guernsey was opened just prior to World War Two. It’s National Forest today.

It was a cavalry training range during its existence, due to the presence of cavalry at Ft. Warren and in the Wyoming National Guard during that period. The nearby presence of the Union Pacific Railroad allowed troops to be deposited at the area by train or to ride there from Ft. Warren.

6. Ft. Yellowstone.

Named after Yellowstone National Park, which it served, the post was established in 1886 for the purpose of administering the National Park, which was a task originally assigned to the Army. Gen. Philip Sheridan dispatched the original cavalry detachment there which accordingly named the post Camp Sheridan, giving us an example of the naming of a Wyoming post after the living honoree, although only barely, as Sheridan was to die the following year at age 57. The post was renamed Fort Yellowstone when it was given permanent status in 1891. The Army occupied the post until 1918 when it was turned over to the National Park Service which had taken over the duties of park administration.

Today its Mammoth Hot Springs in the park. Many of the original buildings remain.

Fort Yellowstone in 1910.

Named after Yellowstone National Park, which it served, the post was established in 1886 for the purpose of administering the National Park, which was a task originally assigned to the Army. Gen. Philip Sheridan dispatched the original cavalry detachment there which accordingly named the post Camp Sheridan, giving us an example of the naming of a Wyoming post after the living honoree, although only barely, as Sheridan was to die the following year at age 57. The post was renamed Fort Yellowstone when it was given permanent status in 1891. The Army occupied the post until 1918 when it was turned over to the National Park Service which had taken over the duties of park administration.

Today its Mammoth Hot Springs in the park. Many of the original buildings remain.

This post had to offer its troops some of the best duty of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries.

7. Ft. Washakie.

This post was named after Chief Washakie of the Shoshone was living at the time and in fact outlived the post, dying at about age 100.

The area has a somewhat complicated history in regard to the establishments of military installations. The first post established there was Camp Augur, which was a subpost of Ft. Bridger. It was established in 1869. Augur was a Mexican war and Civil War general who was the head of the Department of the Platte at the time, giving us another example of the naming of an installation after a living figure, although it was a camp, not a fort. While Camp Augur is regarded as the predecessor of Ft. Washakie, it was actually located where Lander Wyoming is located today. It's purpose was to protect the Shoshones at the Wind River Indian Reservation and it was located at the Indian Agency headquarters. In 1870 the camp was renamed Camp Brown, in honor of Cpt. Frederick Brown who was killed at the Fetterman Fight.

In 1871 the agency headquarters were moved fifteen miles to the north and the Army post went with it. In 1878 the post was renamed Ft. Washakie. The town that developed there is the seat of government for the Wind River Reservation and many of the military buildings remain in use.

This post was named after Chief Washakie of the Shoshone was living at the time and in fact outlived the post, dying at about age 100.

Visit of President Arthur to Ft. Washakie, 1883.

In 1871 the agency headquarters were moved fifteen miles to the north and the Army post went with it. In 1878 the post was renamed Ft. Washakie. The town that developed there is the seat of government for the Wind River Reservation and many of the military buildings remain in use.

This post was one of two (the other being D. A. Russell) which at which the 9th Cavalry was stationed in the state for a time.

This post is unusual in that it was named after an American Indian, and a living one at that. It's occasionally claimed that it provides the only example of this being done, but that is disputed.

This post is unusual in that it was named after an American Indian, and a living one at that. It's occasionally claimed that it provides the only example of this being done, but that is disputed.

Former and closed in the 19th Century.

This list will be incomplete. There were many, many, temporary camps, stations and installations in Wyoming during the frontier period, many of which simply bore the name of where they were. Indeed, my house is quite near one whose exact location is unknown. Some of these which are remembered are because they were more established than the others or they're associated with a specific event.

On this, there's a couple of things we should note.

One is the presence of "stations". During the Civil War the 11th Ohio and 11th Kansas Cavalry, and to an extent the 1st U.S. Volunteers, the latter of which were "galvanized Yankees" who were mostly from Tennessee in Wyoming's case, established a network of stations along the Oregon Trail to protect it and the telegraph line that had gone in. Many of these were existing civilian locations that were thought deserving of protection in any event, but not all of them were. And not all of the existing civilian stations received an Army garrison. This was a change in strategic thinking as it allowed patrols to be shorter and forced Indian parties that might have some destructive intent to deal with a much more extant military presence, even if the number of soldiers at any one station was often very small. The strategy was quite effective.

Not all of the locations for these stations is presently known today. I’m presently within a few miles of three of them, two of which have known locations and one of which doesn’t, but is probably within several hundred yards of my house.

During the same period, and before, the Army also established a lot of camps, quite a few of which were very temporary in nature. Even ones that featured log structures were often only occupied fairly briefly. These bases served campaigns in vast contested territories and had the chance of becoming permanent in some instances, although many did not.

1. Camp Augur and Camp Brown.

See Ft. Washakie

2. Fort Bernard

I'll abstain going into depth on this post, as it was a private American Fur Company trading post near Ft. Laramie. This trading post had a surprisingly long life, existing from 1845 to 1866, when it burned down.

3. Fort Bridger

Ft. Bridger is named for its founder Jim Bridger, who founded it as a trading post in 1842. The post seems to have been sold by a partner of Bridger's to Mormon interests in 1855 during a period of time during which Bridger, who did not get along well with the Mormons, was absent.

The post was burned in 1857 by the Mormons during the Mormon War in order to keep it out of U.S. Army hands, but they wintered there and rebuilt the fort as an Army post in 1858. The Army thereafter occupied it against both of its prior owners until abandoning it in 1878. The Army then reestablished it in 1880, and then closed it again in 1890.

This post was one of the numerous frontier posts established by civilians who named them after themselves. Occupied prior to the Civil War, the Army of that period simply retained the prior name.

Map by William Henry Jackson depicting Pony Express stations. This is posted here as many of the same stations were used by the Army during the Civil War as small military posts.

This list will be incomplete. There were many, many, temporary camps, stations and installations in Wyoming during the frontier period, many of which simply bore the name of where they were. Indeed, my house is quite near one whose exact location is unknown. Some of these which are remembered are because they were more established than the others or they're associated with a specific event.

On this, there's a couple of things we should note.

One is the presence of "stations". During the Civil War the 11th Ohio and 11th Kansas Cavalry, and to an extent the 1st U.S. Volunteers, the latter of which were "galvanized Yankees" who were mostly from Tennessee in Wyoming's case, established a network of stations along the Oregon Trail to protect it and the telegraph line that had gone in. Many of these were existing civilian locations that were thought deserving of protection in any event, but not all of them were. And not all of the existing civilian stations received an Army garrison. This was a change in strategic thinking as it allowed patrols to be shorter and forced Indian parties that might have some destructive intent to deal with a much more extant military presence, even if the number of soldiers at any one station was often very small. The strategy was quite effective.

Not all of the locations for these stations is presently known today. I’m presently within a few miles of three of them, two of which have known locations and one of which doesn’t, but is probably within several hundred yards of my house.

During the same period, and before, the Army also established a lot of camps, quite a few of which were very temporary in nature. Even ones that featured log structures were often only occupied fairly briefly. These bases served campaigns in vast contested territories and had the chance of becoming permanent in some instances, although many did not.

1. Camp Augur and Camp Brown.

See Ft. Washakie

2. Fort Bernard

I'll abstain going into depth on this post, as it was a private American Fur Company trading post near Ft. Laramie. This trading post had a surprisingly long life, existing from 1845 to 1866, when it burned down.

3. Fort Bridger

Ft. Bridger is named for its founder Jim Bridger, who founded it as a trading post in 1842. The post seems to have been sold by a partner of Bridger's to Mormon interests in 1855 during a period of time during which Bridger, who did not get along well with the Mormons, was absent.

Frontiersman Jim Bridger. Bridger was a long lived individual for the dangerous life he lead. Born in Virginia and orphaned in Missouri at age 13, he lived to age 77 and died on his farm in Kansas. He was married three times due the deaths of his spouses, with each of his wives being a Native American. His last was a daughter of Chief Washakie. Of his several children, only one outlived him.

The post was burned in 1857 by the Mormons during the Mormon War in order to keep it out of U.S. Army hands, but they wintered there and rebuilt the fort as an Army post in 1858. The Army thereafter occupied it against both of its prior owners until abandoning it in 1878. The Army then reestablished it in 1880, and then closed it again in 1890.

This post was one of the numerous frontier posts established by civilians who named them after themselves. Occupied prior to the Civil War, the Army of that period simply retained the prior name.

2. Ft. Caspar.

This post amed for Lt. Caspar Collins who was killed at a battle with the Cheyenne at that location in 1865, prior to which it was Platte Bridge Station.

The post location was at a point on the North Platte River that could be forded and it had been used as a temporary military camp prior to Platte Bridge Station prior to the Civil War. In 1849 a ferry was established on the location by the Mormon church. French Canadian entrepreneurs established a bridge there shortly afterwards, and a trading post along with it. When the telegraph line was put through the area, Western Union established a telegraph station there. In 1861 the Army posted troops at the location, given its obvious importance, naming the station after the Bridge. In 1865 a battle was fought across the river from the location in which Lt. Caspar Collins was killed leading a relief party attempting to get to an Army wagon train that was some miles distant and being besieged. The Army then named the post after the late Lt. Collins.

This post amed for Lt. Caspar Collins who was killed at a battle with the Cheyenne at that location in 1865, prior to which it was Platte Bridge Station.

The post location was at a point on the North Platte River that could be forded and it had been used as a temporary military camp prior to Platte Bridge Station prior to the Civil War. In 1849 a ferry was established on the location by the Mormon church. French Canadian entrepreneurs established a bridge there shortly afterwards, and a trading post along with it. When the telegraph line was put through the area, Western Union established a telegraph station there. In 1861 the Army posted troops at the location, given its obvious importance, naming the station after the Bridge. In 1865 a battle was fought across the river from the location in which Lt. Caspar Collins was killed leading a relief party attempting to get to an Army wagon train that was some miles distant and being besieged. The Army then named the post after the late Lt. Collins.

Statue of Collins in Casper, Wyoming.

The location was not named “Ft. Collins”, however, as the lieutenant’s father already had a post named after him, Ft. Collins, which is in northern Colorado. Lt. Collins himself was a member of the 11th Ohio Cavalry which was stationed in Wyoming during the Civil War. His actual post was Sweetwater Station and he just happened to be at Platte Bridge Station when the nearby Battle of Red Buttes developed and he volunteered to lead the relief party. The post was closed as a result of Red Cloud’s War after which the Sioux burned it down. It’s been rebuilt as a very nice city park and historical site.

This is an Oregon Trail memorial at Ft. Casper Wyoming. I somewhat wonder if the medallion on this one came from an older monument, as the medallion is a very common site along the trail on older memorials. At some point prior to World War Two a significant effort was made to place such memorials commemorating the trail, which in many locations had become state highways.

This is an Oregon Trail memorial at Ft. Casper Wyoming. I somewhat wonder if the medallion on this one came from an older monument, as the medallion is a very common site along the trail on older memorials. At some point prior to World War Two a significant effort was made to place such memorials commemorating the trail, which in many locations had become state highways.

This is an even older Oregon Trail Memorial, also located at Ft. Caspar. As can be seen from the monument, it was placed in 1914. During this period, traveling on the trial itself was very common, as nearly every stretch of it was some sort of local road. Indeed, in some parts of Wyoming, this is still the case.

This is an even older Oregon Trail Memorial, also located at Ft. Caspar. As can be seen from the monument, it was placed in 1914. During this period, traveling on the trial itself was very common, as nearly every stretch of it was some sort of local road. Indeed, in some parts of Wyoming, this is still the case.

Once again, these monuments probably really do not belong here, but they are strongly associated with the history of Western movement, which involved a lot of sacrifice of all sorts by all involved.

This post has the distinction of being the first post in Wyoming to be named after a soldier who died in an Indian Wars engagement, signalling what would be a major change in naming conventions that was just beginning.

3. Cheyenne Depot (Camp Carlin).

I'm going to leave this photograph as the description for this one, as its about all I know about a post that I would have regarded as an auxiliary to Ft. D. A. Russell.

3. Deer Creek Station

Deer Creek Station was an Army station on the Oregon Trail that is near the present town of Glenrock. Named simply for its location, its associated with a battle that took place on May 20, 1865 which was actually a series of engagements in the general area of the post. In those actions groups of soldiers were attacked by more numerous parties of Indians but were able to hold off the attacks due to their superior arms. Like Ft. Caspar, this post was abandoned at the end of Red Cloud's War and it was burned by Indians in August, 1866.

I just recently posted an item on this on one or our companion blogs, and hence will include that post here:

In the last couple of days I've put up some photos of Frontier Era Army posts in the state which were taken years ago. All of those were originally posted elsewhere, but a change in how Photobucket operated made them difficult to view, and I was left wondering why I hadn't blogged those photos. I know the reason why, actually. It used to be hard to upload lots of photos onto Blogger. That's changed.

Anyhow, this photograph is new. This is the former location of Deer Creek Station.

The sign itself isn't placed on the exact location, actually. It's near it, more or less, but really a couple of miles away. I'd guess it may be 1 mile to 2 miles from the original post. Anyhow, the sign does a good job of giving the history of the post, which started off as a civilian trading post in 1857 and which was occupied during the Civil War by state troops sent to police the frontier. This post, like a collection of others, was burned by the Indians following the abandonment of the fort in 1866.

3. Ft. Fetterman.

This post was named after the officer of that name killed at “The Fetterman Fight” at a time at which his reputation was not yet tarnished, a process that was at least partially aided by the long efforts of his former commander, Col. Carrington, which is not to say that the fading of Fetterman's star wasn't deserved.

The post was built in 1867 just after the conclusion of Red Cloud's War in which Fetterman had lost his life. It was a major post during its existence, although something about it caused it to have the highest insanity rate in the Frontier Army. At the height of its importance it was a major staging area for the Powder River Campaign of 1876 which would see the Battle of the Rosebud as its major battle, and which occurred just south of Little Big Horn a few days prior to that battle. Following the decline of Indian combat, it was abandoned as unneeded in 1882. Most of the buildings were carted off following the posts closure and were used for the construction of a nearby and fairly infamous town that no longer exists.

4. Ft. Halleck

Ft. Halleck was a large post established on the Overland Trail near Elk Mountain in 1862. It was built to protect that trail, but it was abandoned, in spite of its size, in 1866 when Ft. Sanders was built near Laramie. By that time the Union Pacific Railroad had passed through the area which altered the strategic nature of patrolling this stretch of Wyoming, given as that could now be done with the assistance of rail.

The post was named after Gen. Henry Halleck who was living at the time. He was a career soldier whose career was interrupted by an additional career of being a lawyer. He had a mixed military record, but was good in subordinate commands and brought a spirit of professionalism to the Army. He died in 1874 at age 56.

5. Ft. Phil Kearny.

Principally recalled for the disaster of the Fetterman Fight, and the somewhat redeeming battle of the Wagon Box fight, this post was named after Phil Kearny, a Union general who died at the Second Battle of Bull Run. This post was originally named Ft. Carrington by Col. Carrington, it’s first commander who never outlived the disgrace of the defeat of the Fetterman Fight. The post was burned to the ground by the Cheyenne following Red Cloud’s War.

The post proved to be poorly located and consumed a gigantic quantity of wood, which was one of its downsides. Col. Carrington's career as an Army officer (he'd been a pre Civil War lawyer) was ruined by the events of the Fetterman battle, although he personally managed to escape being court martialed, an event that happened with blistering frequency in the 19th Century Army and which Grant had sought to do after the disaster.

Phil Kearny, we might note, was an unusual Army officer in that he was born into a wealthy family and inherited his family's wealth after his parents passed away while he was young. Raised by grandparents, he had always wished for a military career but went to law school and became a lawyer at his grandparents insistence. He practiced law for four years but, upon the death of his grandfather, he received a commission in the Army and shortly went to France to study cavalry tactics at the famous French cavalry school, the Saumur. While a student there, he actually went to Algeria with the French forces and served as a cavalryman, seeing combat, with the French.

Kearny thereafter lived an odd and adventurous life, twice resigning from the U.S. Army due to a lack of action going on within it, and then rejoining it. He served in the Mexican War and the Civil War, in which he was killed, but he served with the French forces a second time as well, fighting with them against the Austrians.

Perhaps that all explains why this post in Wyoming was named after him. Another already had existed, and ceased to exist, also named in his honor, outside of Washington D. C. Neither post had long existences.

The naming of both posts, however, also shows how people should be considered in the context of their times, while also keeping in mind that absolute truths are universal. Obviously Kearny's Army contemporaries admired him, and he was no doubt supremely interesting to be around. He was highly educated and wealthy, with a taste for adventure. He'd also served in two wars for a foreign power, one of which was a naked colonial enterprise. We wouldn't admire that latter item today, but at least as late as the 1980s there were Americans who seriously entertained, and even served, in foreign wars that were comparable to some extent.

Ft. Phil Kearny was really unusual, we might note, in that it actually had a log post wall around it. Frontier forts are commonly depicted that way in film, but few really were built in that fashion. This one was. Today the location of the former fort is a nice State of Wyoming Park.

I photographed Ft. Phil Keany for another site some years ago, and I just reposted those photographs on our companion blog. Given that, I'm reposting them here as they may be of interest.

Oregon Trail Memorials, Ft. Caspar Wyoming

This is an Oregon Trail memorial at Ft. Casper Wyoming. I somewhat wonder if the medallion on this one came from an older monument, as the medallion is a very common site along the trail on older memorials. At some point prior to World War Two a significant effort was made to place such memorials commemorating the trail, which in many locations had become state highways.

This is an Oregon Trail memorial at Ft. Casper Wyoming. I somewhat wonder if the medallion on this one came from an older monument, as the medallion is a very common site along the trail on older memorials. At some point prior to World War Two a significant effort was made to place such memorials commemorating the trail, which in many locations had become state highways. This is an even older Oregon Trail Memorial, also located at Ft. Caspar. As can be seen from the monument, it was placed in 1914. During this period, traveling on the trial itself was very common, as nearly every stretch of it was some sort of local road. Indeed, in some parts of Wyoming, this is still the case.

This is an even older Oregon Trail Memorial, also located at Ft. Caspar. As can be seen from the monument, it was placed in 1914. During this period, traveling on the trial itself was very common, as nearly every stretch of it was some sort of local road. Indeed, in some parts of Wyoming, this is still the case.Once again, these monuments probably really do not belong here, but they are strongly associated with the history of Western movement, which involved a lot of sacrifice of all sorts by all involved.

This post has the distinction of being the first post in Wyoming to be named after a soldier who died in an Indian Wars engagement, signalling what would be a major change in naming conventions that was just beginning.

3. Cheyenne Depot (Camp Carlin).

I'm going to leave this photograph as the description for this one, as its about all I know about a post that I would have regarded as an auxiliary to Ft. D. A. Russell.

3. Deer Creek Station

Deer Creek Station was an Army station on the Oregon Trail that is near the present town of Glenrock. Named simply for its location, its associated with a battle that took place on May 20, 1865 which was actually a series of engagements in the general area of the post. In those actions groups of soldiers were attacked by more numerous parties of Indians but were able to hold off the attacks due to their superior arms. Like Ft. Caspar, this post was abandoned at the end of Red Cloud's War and it was burned by Indians in August, 1866.

I just recently posted an item on this on one or our companion blogs, and hence will include that post here:

Deer Creek Station, Glenrock Wyoming.

In the last couple of days I've put up some photos of Frontier Era Army posts in the state which were taken years ago. All of those were originally posted elsewhere, but a change in how Photobucket operated made them difficult to view, and I was left wondering why I hadn't blogged those photos. I know the reason why, actually. It used to be hard to upload lots of photos onto Blogger. That's changed.

Anyhow, this photograph is new. This is the former location of Deer Creek Station.

The sign itself isn't placed on the exact location, actually. It's near it, more or less, but really a couple of miles away. I'd guess it may be 1 mile to 2 miles from the original post. Anyhow, the sign does a good job of giving the history of the post, which started off as a civilian trading post in 1857 and which was occupied during the Civil War by state troops sent to police the frontier. This post, like a collection of others, was burned by the Indians following the abandonment of the fort in 1866.

3. Ft. Fetterman.

Ft. Fetterman today.

This post was named after the officer of that name killed at “The Fetterman Fight” at a time at which his reputation was not yet tarnished, a process that was at least partially aided by the long efforts of his former commander, Col. Carrington, which is not to say that the fading of Fetterman's star wasn't deserved.

The post was built in 1867 just after the conclusion of Red Cloud's War in which Fetterman had lost his life. It was a major post during its existence, although something about it caused it to have the highest insanity rate in the Frontier Army. At the height of its importance it was a major staging area for the Powder River Campaign of 1876 which would see the Battle of the Rosebud as its major battle, and which occurred just south of Little Big Horn a few days prior to that battle. Following the decline of Indian combat, it was abandoned as unneeded in 1882. Most of the buildings were carted off following the posts closure and were used for the construction of a nearby and fairly infamous town that no longer exists.

4. Ft. Halleck

Ft. Halleck was a large post established on the Overland Trail near Elk Mountain in 1862. It was built to protect that trail, but it was abandoned, in spite of its size, in 1866 when Ft. Sanders was built near Laramie. By that time the Union Pacific Railroad had passed through the area which altered the strategic nature of patrolling this stretch of Wyoming, given as that could now be done with the assistance of rail.

Gen. Henry Halleck with an extraordinarily unusual kepi or forage cap.

The post was named after Gen. Henry Halleck who was living at the time. He was a career soldier whose career was interrupted by an additional career of being a lawyer. He had a mixed military record, but was good in subordinate commands and brought a spirit of professionalism to the Army. He died in 1874 at age 56.

5. Ft. Phil Kearny.

Principally recalled for the disaster of the Fetterman Fight, and the somewhat redeeming battle of the Wagon Box fight, this post was named after Phil Kearny, a Union general who died at the Second Battle of Bull Run. This post was originally named Ft. Carrington by Col. Carrington, it’s first commander who never outlived the disgrace of the defeat of the Fetterman Fight. The post was burned to the ground by the Cheyenne following Red Cloud’s War.

The post proved to be poorly located and consumed a gigantic quantity of wood, which was one of its downsides. Col. Carrington's career as an Army officer (he'd been a pre Civil War lawyer) was ruined by the events of the Fetterman battle, although he personally managed to escape being court martialed, an event that happened with blistering frequency in the 19th Century Army and which Grant had sought to do after the disaster.

The wealthy, eclectic Phil Kearny, who served in two American wars and two French ones, and who was married twice and divorced once.

Phil Kearny, we might note, was an unusual Army officer in that he was born into a wealthy family and inherited his family's wealth after his parents passed away while he was young. Raised by grandparents, he had always wished for a military career but went to law school and became a lawyer at his grandparents insistence. He practiced law for four years but, upon the death of his grandfather, he received a commission in the Army and shortly went to France to study cavalry tactics at the famous French cavalry school, the Saumur. While a student there, he actually went to Algeria with the French forces and served as a cavalryman, seeing combat, with the French.

Kearny thereafter lived an odd and adventurous life, twice resigning from the U.S. Army due to a lack of action going on within it, and then rejoining it. He served in the Mexican War and the Civil War, in which he was killed, but he served with the French forces a second time as well, fighting with them against the Austrians.

Perhaps that all explains why this post in Wyoming was named after him. Another already had existed, and ceased to exist, also named in his honor, outside of Washington D. C. Neither post had long existences.

The naming of both posts, however, also shows how people should be considered in the context of their times, while also keeping in mind that absolute truths are universal. Obviously Kearny's Army contemporaries admired him, and he was no doubt supremely interesting to be around. He was highly educated and wealthy, with a taste for adventure. He'd also served in two wars for a foreign power, one of which was a naked colonial enterprise. We wouldn't admire that latter item today, but at least as late as the 1980s there were Americans who seriously entertained, and even served, in foreign wars that were comparable to some extent.

Ft. Phil Kearny was really unusual, we might note, in that it actually had a log post wall around it. Frontier forts are commonly depicted that way in film, but few really were built in that fashion. This one was. Today the location of the former fort is a nice State of Wyoming Park.

I photographed Ft. Phil Keany for another site some years ago, and I just reposted those photographs on our companion blog. Given that, I'm reposting them here as they may be of interest.

Ft. Phil Kearny

5. Ft. Laramie.

Named for its location on the Laramie River this post started off as a civilian trading post named Fort William. William Sublette founded the post in 1833/1834 and the post was initially named after him. In 1841 the post was sold to the American Fur Company in 1841 and renamed Fort John in honor of John B. Sarpy, a partner in that company. In 1849, following the end of the Mexican War, it was purchased by the U.S. Army and renamed Ft. Laramie, reflecting the fact that the post was routinely called Fort John on the Laramie River. Laramie of the name was a French fur trapper who had the misfortune of disappearing in the location. Jacques LaRamy, (by some spellings) donated his name, by that method, to the state and as a result the fort, two towns, a river, a county, a mountain range, and a geologic event are all named for him.

The post was a major Army post for decades and one of the most significant in the region. It's importance declined, however, after the transcontinental railroad became fully established and then the end of active Indian campaigns in Wyoming further decreased its role. The post was abandoned in 1889 and decommissioned in 1890. Even though the Army removed fixtures of use in 1890 and locals further stripped the post after it was closed, the base was so well established that much of it remained when it was made a National Historic Site in 1931.

Named for its location on the Laramie River this post started off as a civilian trading post named Fort William. William Sublette founded the post in 1833/1834 and the post was initially named after him. In 1841 the post was sold to the American Fur Company in 1841 and renamed Fort John in honor of John B. Sarpy, a partner in that company. In 1849, following the end of the Mexican War, it was purchased by the U.S. Army and renamed Ft. Laramie, reflecting the fact that the post was routinely called Fort John on the Laramie River. Laramie of the name was a French fur trapper who had the misfortune of disappearing in the location. Jacques LaRamy, (by some spellings) donated his name, by that method, to the state and as a result the fort, two towns, a river, a county, a mountain range, and a geologic event are all named for him.

The post was a major Army post for decades and one of the most significant in the region. It's importance declined, however, after the transcontinental railroad became fully established and then the end of active Indian campaigns in Wyoming further decreased its role. The post was abandoned in 1889 and decommissioned in 1890. Even though the Army removed fixtures of use in 1890 and locals further stripped the post after it was closed, the base was so well established that much of it remained when it was made a National Historic Site in 1931.

In terms of names, it's one of two posts in Wyoming that were basically named after thier locations, although in this case the name was simply inherited from prior use. If a person views Fort Laramie as having been called that as a contraction of Fort John on the Laramie River, that's the case. Of course, by extension, as noted, Jacques La Ramee (another spelling) contributed his name. La Ramee was a Quebecois Metis who disappeared in the area in 1821 at age 37. His death has been attributed to falling through ice and from an Arapaho raid, but nobody really knows what happened to him.

6. Ft. McKinney

There were two posts named this, both named after 2nd Lt. John McKinney, who went down in a hail of hostile gunfire in the Dull Knife Battle in 1877. Given that he was a young officer at the time, he is somebody that I don't know anything else about. He was assigned to the 4th Cavalry and was likely fairly new to the Army at the time.

The first post named after McKinney had been first named Cantonment Reno, which was established in 1876 as a staging area during the Powder River Expedition. As a Cantonment the post, which was the second one located at that spot in the Powder River Basin was the second one in that location named Reno, as will be seen below. It was renamed and repurposed as a fort the following year after McKinney's death, but the location proved to be a poor one for a sustained presence due to the lack of resources most of the year and the decision was made to move the garrison across the Powder River Basin in 1878. When the new garrison was built, it retained the name of the prior one, which of course had only recently been named. The new Ft. McKinney was manned until 1894 when it was closed. In 1903 the grounds were turned over to the State of Wyoming and they are used today as the state's veteran's home.

Ft. McKinney played a notable role in Wyoming's history when cavalry form the location was dispatched to intervene in the Johnson County War.

Cantonment Reno is one of those locations I've photographed for another reason, and I just reposted those photographs on our companion blog. Given that, I'll repost that item here:

The first Ft. McKinney, or Cantonment Reno, today.

The first post named after McKinney had been first named Cantonment Reno, which was established in 1876 as a staging area during the Powder River Expedition. As a Cantonment the post, which was the second one located at that spot in the Powder River Basin was the second one in that location named Reno, as will be seen below. It was renamed and repurposed as a fort the following year after McKinney's death, but the location proved to be a poor one for a sustained presence due to the lack of resources most of the year and the decision was made to move the garrison across the Powder River Basin in 1878. When the new garrison was built, it retained the name of the prior one, which of course had only recently been named. The new Ft. McKinney was manned until 1894 when it was closed. In 1903 the grounds were turned over to the State of Wyoming and they are used today as the state's veteran's home.

Ft. McKinney played a notable role in Wyoming's history when cavalry form the location was dispatched to intervene in the Johnson County War.

Cantonment Reno is one of those locations I've photographed for another reason, and I just reposted those photographs on our companion blog. Given that, I'll repost that item here:

Cantonment Reno (Ft. McKinney)

7. Ft. Reno.

This post is mentioned immediately above and, as noted, the name was used twice, making it have an odd legacy with Ft. McKinney, which one of the Reno posts became, as that name was also used twice.

Both Reno installations were named after Maj. Gen. Jesse Lee Reno, a Union officer killed early in the Civil War. He was not related in any fashion to Marcus Reno of Little Big Horn fame. He was born in what was then Wheeling Virginia, and which became Wheeling, West Virginia, during the Civil War, making him an officer who hailed from a state that was severed in two by the Civil War. He'd graduated from West Point prior to the Mexican War and had served continually, earning a reputation of being a "soldier's soldier". He was killed by friendly fire while in advance of his troops reconnoitering the area, when one of his own soldiers mistook him for a Confederate.

The first Ft. Reno had originally been called Ft. Connor as it was established by Patrick Connor, a regional commander in Wyoming during the Civil War. It was renamed for Reno after only bearing the name Ft. Connor in October and November 1865, the month of its establishment. Like Ft. Phil Kearny, it was unusually for a Wyoming post as it had actual walls, which most frontier posts did not.

This post is mentioned immediately above and, as noted, the name was used twice, making it have an odd legacy with Ft. McKinney, which one of the Reno posts became, as that name was also used twice.

Jesse L. Reno.

Both Reno installations were named after Maj. Gen. Jesse Lee Reno, a Union officer killed early in the Civil War. He was not related in any fashion to Marcus Reno of Little Big Horn fame. He was born in what was then Wheeling Virginia, and which became Wheeling, West Virginia, during the Civil War, making him an officer who hailed from a state that was severed in two by the Civil War. He'd graduated from West Point prior to the Mexican War and had served continually, earning a reputation of being a "soldier's soldier". He was killed by friendly fire while in advance of his troops reconnoitering the area, when one of his own soldiers mistook him for a Confederate.

Patrick Connor

8. Ft. Sanders

Ft. Sanders was surprisingly a Civil War contemporary of the other Civil War era forts and posts noted here. The post is generally obscure, even though it had a longer life than its contemporaries.

Ft. Sanders was established near where Laramie now is in 1866 to guard the Overland Trail, but its location meant that it was located on the path of the Transcontinental Railroad and therefore its purpose converted to guarding it fairly quickly. It soon bordered Laramie, which was established in 1869 with the establishment of the railroad. It started to become redundant with the establishment of Ft. D. A. Russell, but it was none the less manned until 1882.

The post was named after Gen. William P. Sanders who was killed at the Siege of Knoxville, although that was its second name. Sanders was a West Point graduate who had barely graduated as the Superintendent of West Point at the time, Robert E. Lee, recommended his dismissal. The Secretary of War at the time, Jefferson Davis, who was also his cousin, intervened and saved Sanders career. He was killed in action in Kentucky at age 30, in 1863. A position in the campaign in which he was killed was also named Ft. Sanders.

This post was originally Ft. John Buford, who died of illness also in 1863. Buford, like Sanders, had southern connection and was also from Kentucky, and has also remained loyal to the Union. Prior to the war he had seen frontier service as a dragoon and his military career had a lasting legacy in teh U.S. Army as he is associated with the development of bugle calls. He died of typhus while serving in the field.

Buford remains remembered in the Army and the M8 light tank, that was adopted but not put into service, was named after him. He also had a fort named after him in what is now North Dakota which was manned from 1872 until 1895. The town of Buford, Wyoming, is likewise named after him. His legacy is oddly cut short, much like his life, in the things that were named after him.

Ft. Sanders was surprisingly a Civil War contemporary of the other Civil War era forts and posts noted here. The post is generally obscure, even though it had a longer life than its contemporaries.

Not much remains of Ft. Sanders today.

William P. Sanders

The post was named after Gen. William P. Sanders who was killed at the Siege of Knoxville, although that was its second name. Sanders was a West Point graduate who had barely graduated as the Superintendent of West Point at the time, Robert E. Lee, recommended his dismissal. The Secretary of War at the time, Jefferson Davis, who was also his cousin, intervened and saved Sanders career. He was killed in action in Kentucky at age 30, in 1863. A position in the campaign in which he was killed was also named Ft. Sanders.

John Buford

This post was originally Ft. John Buford, who died of illness also in 1863. Buford, like Sanders, had southern connection and was also from Kentucky, and has also remained loyal to the Union. Prior to the war he had seen frontier service as a dragoon and his military career had a lasting legacy in teh U.S. Army as he is associated with the development of bugle calls. He died of typhus while serving in the field.

M8 Buford

Buford remains remembered in the Army and the M8 light tank, that was adopted but not put into service, was named after him. He also had a fort named after him in what is now North Dakota which was manned from 1872 until 1895. The town of Buford, Wyoming, is likewise named after him. His legacy is oddly cut short, much like his life, in the things that were named after him.

9. Ft. Fred Steele.

Named for Frederick Steele who rose to the rank of Maj. Gen. during the Civil War but who died as the result of an accident while experiencing ill health in 1868. Somewhat fittingly, this is now the most depressing historical site in the state.

Ft. Fred Steele was built in 1868 specifically to provide security to the transcontinental railroad and, after its construction, was part of a three fort network, including Ft. Sanders and Ft. D.A. Russell that served that purpose. The garrison of the fort in fact did use the railroad for transportation when needed, and its location, that was highly isolated, but at the same time centrally located on the rail line, made such deployments ideal. The post dispatched troops as needed as far away as Chicago and deployed to put down the the anti Chinese riots in Rock Springs when that occured. The garrison fought a major engagement in the White River War in 1879 at Milk Creek, Utah, that went very badly leading to the unit being besieged for a period of days necessitating additional deployments from the post and Ft. D.A. Russell. The post was no longer necessary by the mid 1880s and it was abandoned in 1886.

Named for Frederick Steele who rose to the rank of Maj. Gen. during the Civil War but who died as the result of an accident while experiencing ill health in 1868. Somewhat fittingly, this is now the most depressing historical site in the state.

Ft. Fred Steele was built in 1868 specifically to provide security to the transcontinental railroad and, after its construction, was part of a three fort network, including Ft. Sanders and Ft. D.A. Russell that served that purpose. The garrison of the fort in fact did use the railroad for transportation when needed, and its location, that was highly isolated, but at the same time centrally located on the rail line, made such deployments ideal. The post dispatched troops as needed as far away as Chicago and deployed to put down the the anti Chinese riots in Rock Springs when that occured. The garrison fought a major engagement in the White River War in 1879 at Milk Creek, Utah, that went very badly leading to the unit being besieged for a period of days necessitating additional deployments from the post and Ft. D.A. Russell. The post was no longer necessary by the mid 1880s and it was abandoned in 1886.

Fred Steele himself was a career officer who had served in the Mexican War and the Civil War with distinction. He saw immediate service in Texas and the Northwest following the Civil War but took medical leave in 1867. He died due to an apoplectic fit that caused him to fall from a buggy in 1868. The post, therefore, was named for him the very year he died.

10. Ft. Supply,

Ft. Supply will be mentioned here, but as it was a private Latter Day Saints fort, and never an Army post, we'll just do that. It was built in 1853 in what is now Uinta County and abandoned along with Ft. Bridger in 1857 during the Mormon War. Unlike Ft. Bridger, the Army did not rebuild it but only occupied the position briefly.

Ft. Supply will be mentioned here, but as it was a private Latter Day Saints fort, and never an Army post, we'll just do that. It was built in 1853 in what is now Uinta County and abandoned along with Ft. Bridger in 1857 during the Mormon War. Unlike Ft. Bridger, the Army did not rebuild it but only occupied the position briefly.

11. Sweetwater Station.

Sweetwater Station was one of the numerous stations occupied by the 11th Ohio and 11th Kansas Cavalry during the Civil War, during that period of time in which they patrolled the Oregon and Overland Trails. This station was a significant one on the Oregon Trail. Lt. Caspar Collins, who died at the Battle of Platte Bridge Station, was actually stationed at Sweetwater Station.

Perhaps somewhat fittingly, the location today remains a rest stop on the highway.

The station was on the Sweetwater River and was named after it.

Perhaps somewhat fittingly, the location today remains a rest stop on the highway.

The station was on the Sweetwater River and was named after it.

12. Richard’s (Reshaw's) Bridge.

This station was informally but not officially named for the bridge and trading post owned by the individual of that name and had an occasional military presence dating back to November, 1855 when troops were first stationed there and the post was named Ft. Clay. That following March the post was renamed Camp Davis and then abandoned that November after having been occupied for one year. The post was occupied again in 1858 during the Mormon War, this time as Camp Payne, but then once again abandoned in 1859.

This station was informally but not officially named for the bridge and trading post owned by the individual of that name and had an occasional military presence dating back to November, 1855 when troops were first stationed there and the post was named Ft. Clay. That following March the post was renamed Camp Davis and then abandoned that November after having been occupied for one year. The post was occupied again in 1858 during the Mormon War, this time as Camp Payne, but then once again abandoned in 1859.

Richard was Quebecois and therefore the pronunciation of this name in the French lead to the phonetic "Reshaw". The bridge was an important one in Central Wyoming on the Oregon Trail but it drew competition from Guinard's bridge, owned by fellow Quebecois, which was opened in 1859. The Mormon ferry was located at that location as well. Because of this the importance of Reshaw's Bridge declined and the Army did not reestablish a regular garrison at the bridge when the 11th Ohio and 11th Kansas occupied the stations during the Civil War. It was important during the 1850s, however, and the Army garrisoned it successively each time there was a need to, renaming the garrison three times.

So there we have the Wyoming installations. What does that tell us about how the Army named its installations over the years? We'll look at that next.

_________________________________________________________________________________

So there we have the Wyoming installations. What does that tell us about how the Army named its installations over the years? We'll look at that next.

_________________________________________________________________________________